He invited me to lunch and of course I accepted. I broke the news that he could relax; there wouldn’t be any more columns about him. The look of disappointment on his face almost made me laugh.

His response: “Good. Now you’ll stop calling me a liar in public.”

Yeah, right.

Then he said, “I told you that people don’t want to hear those stories.”

Al contrario, Cowboy. It seems they do.

I tried to work a few more stories out of him, but he’s wise to me now. So I have to go with what I know. And I was there for this one.

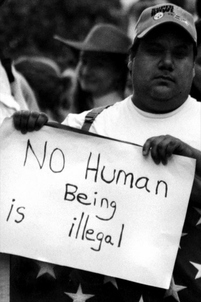

What we didn’t know at the time was that the Border Patrolman who had taken such a dislike to us was a vindictive man and he was the boss. Before I continue, I want to say that this is about only one man, not the Border Patrol in general.

The cowboy had been picked up on numerous occasions and was returned to the border each time. He’d worked at the fluorspar mine in the Christmas Mountains, on Terlingua Ranch, and in Odessa, Midland, and Lajitas. He said he’d never been mistreated once by any Border Patrolman and he never feared them. My point is that in any profession there can be one who gives the whole bunch a bad rep.

I could tell you the man’s name, but it doesn’t matter. He’s long gone from the job and also the planet. Suffice it to say that the night of the murder, which was later determined to be an accidental shooting, he let personal hatred supersede his professional duties.

Lajitas was similar to a large plantation during the days of slavery. In the Big House, some inhabitants were “less than” others. The workers, no matter our background or color, were in it together. We were tight. At the Big House they professed, “But we love our Mexicans.” Read, we love our cheap labor.

Border Patrol raids were common, but back then it was like a big game. A few green-uniformed men would show up in town. Radios, walkie-talkies, and telephones would hum with the news. La Chota!

The Border Patrol only came because they were supposed to and they sometimes took men away if they were slow enough to get caught. Or if the officers managed to surprise them. On raid days we hid people in all the nooks and crannies of the resort while the outside workers ran for the hills. I said it was like a big game, but I didn’t say everyone enjoyed it.

Four times they came in succession and it became evident they were after my cowboy. They asked about him at the Big House and they chased him. He escaped into the mountains or to the Rio, and he was fast. This became a rock in the boot because the boss was telling them to get That Mexican.

The manager of Lajitas called me in to say that this problem with the Border Patrol was disrupting the work schedule. I asked what I was supposed to do about it. Did he expect me to tell him not to run? No. He was one of the best workers. What, then? He didn’t know.

The Border Patrol figured it out pronto. The next day they returned with the boss and he caught my cowboy himself. He yelled to stop or he’d shoot him. That was a tactic they hadn’t used on him before and it worked.

I was at home and received this call from the front desk: “They have him in front of the hotel.” Nobody had to tell me who had nabbed who. I ran as though they were chasing me.

They had put him in back of a Suburban that was barred. There were a few other stricken-faced guys with him. It was a sight that tore at my heart. I was about to start sobbing, but he gave a tiny grin and shrugged. He believed he’d be back in a few days. I knew it would not be that simple.

What followed was a long, drawn-out mess. He was prosecuted because he’d run away and in doing that, he had “endangered” an officer of the Law. The game had reached a new level and the opponent held all the pieces.

I was forced to hire an immigration attorney. He said if I intended to marry the man, and I did, I had gone about it backwards. He explained that you’re supposed to get a “Sweetheart Visa” first. Great. Everywhere but within the law, falling in love comes first. The bottom line, law-wise, was that he should have stayed in Mexico until we were married. I didn’t bother to point out that if he’d stayed there I would never have met him.

The cowboy was jailed in Alpine, then Pecos, and was later moved to a big holding facility in El Paso. He was formally deported and then came back on a provisional visa. Doing it the wrong way cost us plenty. They slammed door after door.

The great news is that love won. We made it through the wall.

* * *

We saw our Border Patrol nemesis a year or so later when we were eating in the Badlands Restaurant in Lajitas. My husband was holding our tiny newborn daughter and the sun was shining brightly on both of them.

The Bad Man came in with two other men and they all glared at us.

My wise cowboy said, “Don’t look at him, Honey. He’s too small and sad to be part of our world.”

That was true; I knew it was, but I was not so forgiving. I said, “I wish I could hurt him.”

“You already did.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed